This might sound like a simple question, but it might not be as straightforward as you think. There is actually more than one type of money. Indeed, there are at least four.

This is perhaps best described in a fascinating book by American economist Joseph Wang. The book is Central Banking 101. It is an insider’s account of how central banks work, given that Wang spent five years working for the US Federal Reserve – the USA’s central bank.

While Wang writes from the US perspective, Australia has a similar central banking system. So, what Wang writes relates directly to our situation as well.

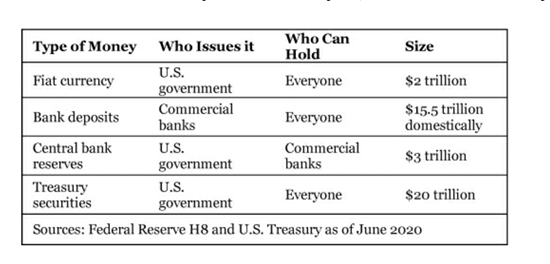

Wang starts out with a very well-written description detailing how, in countries like Australia and the US, which use fiat currencies and central banks, there are really four types of money. These types are technically different, but because they can be easily exchanged with each other, they can essentially be seen as all being variations of the same thing.

The four types are shown in this picture. The fourth column is the size of this type of money in the US at the time Wang wrote:

Source: Wang, J. Central Banking 101

The first type of money is listed as fiat currency. This is notes and coins. In Australia, these are of course issued by the Australian Government. As with the US, anyone can hold Australian dollars. Even people outside of Australia.

The next type of money is bank deposits. These deposits can come into existence by account holders presenting their coins and notes to their bank. When they do this, the bank puts the cash in the safe and increases the amount held in the customer’s account.

But passing cash and coins over the counter creates only a very small portion of total bank deposits. Most bank deposits are created by banks themselves when they make loans to customers. That’s right, when you take out a loan, the chances are that the money you borrow is newly created for that purpose. This is called horizontal money creation.

When you take out a loan, your bank does two things. Firstly, it creates a deposit in your account. This deposit is an asset from your point of view and a liability from the bank’s point of view. Secondly, the bank simultaneously creates a debt to them in your name. This is a liability from your point of view and an asset from the bank’s point of view.

So, when the loan is first drawn, you have an asset (money in your account) and a debt of the same size (the loan liability). Your net assets are not changed. (Net assets are assets minus liabilities).

Once the money is deposited into your account, you can do one of three things with it. You can simply leave it in your account. This is unlikely – why borrow money and not use it (especially when you have to pay interest)?

A second option is to withdraw some of the money as cash – notes and coins. This is an example of how the two types of money – bank deposits and cash – are interchangeable. Let’s say you withdraw ten $100 notes from an ATM. The value of your bank deposit goes down by $1,000, but you have $1,000 in cash. You have swapped the two types of money.

The third, and far more likely option, is that you electronically transfer your bank deposit into the bank account of some other person. If, for example, your loan is a home loan, you will transfer your bank deposit to the person selling the home. So, the value of your bank deposit goes down and the value of the vendor’s bank deposit goes up. This is the usual way in which loan-financed bank deposits are spent.

Imagine that the vendor uses the same bank that you do. In that case, it is a relatively easy thing for the bank to transfer the deposit from your account to the vendor’s account. They simply reduce the amount in your deposit account and increase the amount in the vendor’s account. It is all done with keystrokes.

Now, remember that your bank deposit is a liability for the bank. When you make a payment, the bank decreases it’s liability to you and increases it’s liability to whichever account has ‘received’ the money. It swaps a debt to you for a debt to someone else.

Things get a bit more interesting when the vendor uses a different bank. In that case, the bank cannot simply transfer your deposit to the vendor’s bank account, because they do not have access to the vendor’s account. Instead, your bank has to transfer some money to your vendor’s bank. To do this, they use the third type of money – reserves held at the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Each licenced bank has a reserve account with the RBA. When money needs to transfer from one bank to another, the actual transaction is made using the money in these reserve accounts.

Let’s say you bank with Westpac and you pay $100,000 to a vendor who banks with ANZ. Westpac instructs the RBA to transfer $100,000 of its reserves to the ANZ. Once it receives these reserves, the ANZ will deposit the same amount into the deposit account of the vendor. (Although, read on below for a fuller explanation of what happens when more than one person transfers money between banks).

The fourth type of money is what Wang calls a Treasury Security. We have these too. They are issued by the Commonwealth Treasury, which is the Government department that Jim Chalmers is currently running.

The Commonwealth Treasury also has a reserve account at the RBA. When it issues a bond, the bond is usually sold to someone who uses their reserves with the RBA to finance the purchase. When this happens, Treasury’s reserve account goes up and the account of the bond purchaser goes down – just like what happens if you pay money to someone who uses the same bank as you.

Then, when Treasury needs to make a payment, it transfers its reserves to the bank in which the recipient of the payment holds a deposit account. Let’s say you work as a Commonwealth public servant and you are paid a net salary of $5,000 a month. Treasury transfers $5,000 of its reserves to your bank (Westpac) and Westpac in turn increases the amount in your deposit account by $5,000. This is known as vertical money creation.

In reality, there are millions of transfers between banks, and transfers between Treasury and banks, each day. Reserves are not exchanged every single time a transaction takes place. Instead, there is one overall ‘reserve exchange’ at the end of each trading day. If, at the end of the day, Westpac customers have received as much money from ANZ customers as other Westpac customers have paid to other ANZ customers, reserves don’t move at all.

For example, if Westpac has to transfer $50m to the ANZ and the ANZ has to transfer $51m to Westpac, then in reality the ANZ just transfers the difference ($1m).